The Mother Court: A Newsletter of the SDNY Chapter of the Federal Bar Association. Spring 2021.

CLICK HERE TO ACCESS THE NEWSLETTER!

THE MOTHER COURT

A N E W S L E T T E R O F T H E S D N Y C H A P T E R O F T H E F E D E R A L B A R A S S O C I A T I O N

S P R I N G 2 0 2 1 • V O L U M E 1 • I S S U E 2

A M E S S A G E F R O M T H E P R E S I D E N T

“ Here comes the sun, and I say, it’ s alright” – the Beatles

Dear SDNY Chapter Members, Colleagues, and Friends:

Welcome to the Spring issue of The Mother Court. I love this time of the year. And, now that we are (or soon to be) all eligible for the Covid-19 vaccination, we can relax, recharge, and reconnect with family and friends.

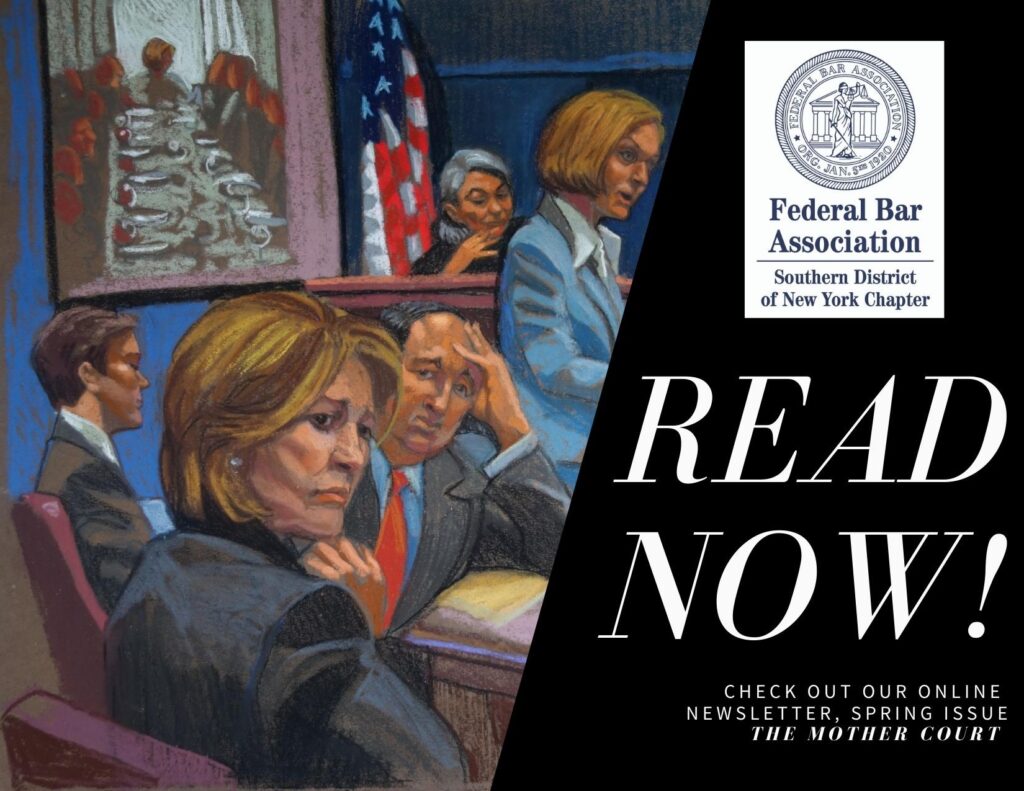

In this issue, there is a discussion on the appropriateness of diversity in board governance; a glimpse into the life of an SDNY courtroom artist and a showcase of her amazing art; information about the humanitarian exception to the ethics rule in representing indigent clients; and a celebration of the two new Bankruptcy judges appointed in our district. We also spotlight past events and offer a preview of upcoming programs.

We hope you enjoy this issue, as much as we enjoyed working on it. Look for our Summer issue in June!

Nancy Morisseau, President SDNY Chapter

M A N D A T I N G D I V E R S I T Y I N C O R P O R A T E G O V E R N A N C E I S A G O O D T H I N G

B Y : K A M A N T A C . K E T T L E *

I will never forget as a junior associate in “ Big Law,” interviewing a law student for a summer associate position at my firm. At the end of the interview, the candidate rightfully asked about the firm’ s commitment to diversity. At the time, large law firms were grappling with disappointing statistics surrounding the lack of diversity in the partnership ranks, despite targeted efforts to recruit underrepresented minorities into summer associate classes— like the one this candidate hoped to join. I gave an honest answer that included my observations about the dearth of minority counsel and partners at the firm, but what I believed were the honest intentions of members of the firm to improve upon its record of diversity through various initiatives.

Fast forward a decade and the diversity statistics at law firms remain, by and large, unchanged. And yet, corporate law firms are not alone. An article published in Fortune magazine noted that in the history of the Fortune 500 list, there have been only 19 Black CEOs out of a total 1, 800 chief executives, with numbers expected to decline in the coming years.

“[T]he Proposal is not a diversity quota in that it does not mandate a certain board constitution, but merely requires companies to disclose the level of diversity on their boards and, to the extent such levels fall short of Nasdaq’s objectives, explain why.”

Thus, when Nasdaq introduced a Proposal mandating board- level diversity disclosures on December 1, 2020, many applauded the idea. As initially presented to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the Proposal would have required all Nasdaq-listed companies to publicly disclose board-level diversity statistics within one year of the rule’ s approval or face having their securities delisted from the exchange. Moreover, the proposed rule set clear diversity objectives by requiring all companies to have at least one diverse director on its board within two years of the rule’ s approval, and at least two diverse directors within four to five years of the rule’ s approval, with regular reporting requirements to ensure that those objectives continue to be met. Companies not in a position to meet the rule’ s board composition objectives within the required timeframes would be subject to delisting on the Nasdaq unless they publicly explained their reasons for not meeting the rule’ s objectives.

The Proposal made headlines last year for being the first of its kind, requiring federal approval by the SEC. Despite receiving overwhelming support, it also made headlines in conservative news outlets for proposing “ illegal racial quotas”, and “ push[ing] companies to hire fewer white, straight men.” In an Op-Ed written by Nasdaq’ s CEO, Adena Friedman, in the Wall Street Journal, she is clear: the Proposal is not a diversity quota in that it does not mandate a certain board constitution, but merely requires companies to disclose the level of diversity on their boards and, to the extent such levels fall short of Nasdaq’ s objectives, explain why. Whether or not one agrees with Ms. Freidman’ s characterization of the Proposal, is less important than why such a rule is needed. Diversity, equity and inclusion make common sense. A series of reports by consulting firm McKinsey & Company establish that there is “ a positive, statistically significant correlation between executive team diversity and financial performance” in terms of both gender diversity and ethnic/cultural diversity.

On February 26, 2021, Nasdaq filed an amendment to its diverse director proposal, introducing more flexibility into the rule. On March 10, 2021, the SEC posted a notice on its website deferring decision on Nasdaq’ s Proposal while soliciting further public comment. Some would say that Nasdaq’ s amendments to the diverse director rule proposal are appropriately sensitive to the circumstances of particular corporations. Perhaps. However, the amendments should also be recognized as a retreat from the principle that inclusivity and representation in governance need to be critical priorities.

Kamanta C. Kettle is a Senior Associate at Dunnington Bartholow & Miller LLP. In 2020, she was named to the National Black Lawyers List of Top 40 Under 40 Lawyers.

* The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any other agency, organization, employer or company.

L I F E O F A C O U R T R O O M A R T I S T :

I N S I G H T S I N T O T H E H U M A N C O N D I T I O N

B Y : C H R I S T I N E C O R N E L L

“ OH NO! Not just Federal Court!” This was my wailing lament in 1989, upon discovering that I would be sketching only in federal courts. State court had been my bread and butter since 1975, when I began drawing primarily for local TV news. I lived and breathed a steady diet of sensationalist headlines and “ whodunits” such as David Berkowitz “ The 44 Caliber Killer,” Bernard Goetz, “ The Subway Vigilante,” or Robert Chambers, “ The Preppie Killer!”

While I had drawn plenty of federal court cases too (e. g., “ The Pizza Connection,” a criminal trial against the Sicilian and American mafia, with its gorgeous geographical charts and “ Abscam,” the FBI sting operation leading to the conviction of seven members of Congress, with its tiny video screens of federal agents in Arab dress soliciting bribes from Congressmen), now I stood to be sentenced to all manner of sexless white collar crime, tax evasion, insider trading, political corruption, RICO, with its fine nets and criminal enterprise hierarchy photos pasted pyramid style on illustration boards. So, I had thought. I was wrong. There was plenty of human malfeasance and fatal flaws to delve in federal court.

I sketched and had front row seats to the takedown of the Mafia, the mob bosses (John Gotti, especially), who on the surface were glossy demigods, self-proclaimed Robin Hoods to their community and gentlemen in fancy suits with smooth manners. But, underneath that flashy bravado, what bonded them was murder and greed. The decade of terror trials opened an alarming window into the grievance fallout of US power broker relations in the Middle East.

As an artist, there were many joys. All those black beards, and the beauty of traditional Islamic garb, as well as truly horrific exhibits of crumpled buildings and fiery images of carnage. I drew a fireball from a video of an explosion, yellow and orange off a grainy screen. Some images were so dark they were unforgettable, like a gruesome gray crime scene photo of a man who had been blown up in the seat of the downed Philippine airliner; he had lost his lower half-body.

At the 1993 World Trade Center (WTC) bombing trial, at times the courtroom was festooned with twisted pieces of metal from the WTC girders resembling a Constantin Brâncuși or a David Smith sculpture. There was a parade of heart wrenching witnesses who were survivors — one, a woman who had lost her sight due to the tragedy. In the drug trafficking trial of El Chapo, the escapades of ingenuity and deceit were worthy of a James Bond thriller. It had all the makings of a great short story, adventure, dark cunning, murder, hints at complicity by political royalty, and sex! Federal Court has offered me an astonishing tableau to explore human fault lines.

THE NEW HUMANITARIAN EXCEPTION:

FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE TO INDIGENT LITIGATION CLIENTS

by James B. Kobak, Jr.

Last June, the New York Courts added a so-called “humanitarian exception” as Rule 1.8(e)(4) of the New York Rules of Professional Conduct (“RPC”). The new Rule permits lawyers representing indigent clients in litigation on a no-fee basis to provide financial assistance for needs beyond the costs and expenses of litigation permitted by other sections of Rule 1.8. Any reader representing indigent clients, whether through a legal service program, law school clinic or individual or law firm pro bono efforts, needs to be familiar with the new exception. The Administrative Board of the state court adopted the rule on an unusually accelerated basis at the urging of bar leaders concerned about the ravages of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Because the Rule is recent, it does not appear in all versions of the RPCs available on line or in any but the most recent print versions of the RPCs. Further, the Comments that usually accompany Rule 1.8 in available sources have not yet been updated to reflect the new provision. The New York State Bar Association House of Delegates previously voted to adopt a version of the Rule and Comments slightly different from the Rule adopted by the courts and is being asked to approve final Comments at its meeting in early April.

The Humanitarian Exception

RPC 1.8(e)(4) now permits a lawyer representing a client on a no-fee basis to provide other assistance such as help with food, medical care, rent or other urgent necessities, subject to a few important provisos intended to allay concerns about personal conflicts and considerations akin to champerty. Thus, a lawyer may not promise or advertise the possible availability of such assistance. Nor may this kind of assistance—unlike that for expenses and costs of litigation—take the form of a loan or support that would cause the client to be beholden to the lawyer. The courts also added language to the originally proposed rule to specify (consistent with policies and accounting procedures that most legal service providers already have in place) that assistance may not be provided from funds raised by legal service providers for legal services assistance to clients.

The American Bar Association adopted a similar Rule and comments to its Model Rules in August but with some differences, including a limitation that the assistance be for “modest gifts” for “food, rent, transportation, medicine and other basic living expenses.” The gist of some of this language, but not the limitation of assistance to “modest gifts,” is incorporated in the Comments that the State Bar is being asked to confirm. As provided in the ABA rule, and explained in the COSAC proposed Comments, cases undertaken “without fee” may include cases taken on originally on a pro bono basis even though a statutory attorney’s fee is eventually awarded, just as they are treated for purposes of the rules and comments dealing with pro bono representation.

Centralizing an Organization’s Approach

Some often-overlooked features of a humanitarian exception are the difficult position in which it can place lawyers regularly representing the indigent, virtually all of whose clients desperately need financial assistance, and the disparate treatment that clients may receive depending on the policies and financial wherewithal of the lawyer they happen to find or to whom their case is assigned. The proposed COSAC comments, previously approved by the State Bar, emphasize that financial assistance is not part of a lawyer’s duty when representing an indigent client and that the Rule does not prohibit organizations from having centralized policies to determine whether and in what circumstances to offer financial assistance. The proposed Comments also clarify that nothing in the Rule prevents an organization or individual lawyer from helping an indigent client find other sources of financial assistance or discussing what effects financial assistance from the lawyer or other sources may have on the client’s other interests such as the right to other benefits. Many lawyers who regularly represent the indigent consider knowledge about sources of financial assistance and the consequences of receiving it a key part of their function. With the new Rule in place, firms and corporations with pro bono litigation programs in New York need to consider adopting centralized policies and developing information resources for their lawyers and volunteers so that those lawyers and volunteers can deal as effectively and fairly as possible with the needs of their clients critical to keeping claims or defenses, and in extreme cases even the clients themselves, alive.

James B. Kobak, Jr. is Senior Ethics Counsel at Hughes Hubbard & Reed and a member of the New York State Bar Association’s Committee on Standards for Attorney Conduct (COSAC).